Seville is a large city, busier and more hectic than Malaga or Cordoba. Our host informed us that the Holy Week/ Semana Santa celebrations begin here on the Friday before “Easter Week” and advised us to plan ahead, as things would get busy. We had not yet booked transportation onwards to Cadiz and now discovered all the trains were full! Fortunately, we were able to find seats on a bus running between Seville and Cadiz.

Having sorted that out, we decided against visiting the “over the top” ( in Paul’s view) baroque Iglesia Colegial del Divino Salvador and went for tapas next door instead. The highlight was the Payoyo cheesecake! The cheese is a mixture of goat and sheep cheese from the Sierra de Grazemela, to the east. On our wanders later, we passed a church where we were able to view one of the Semana Santa processional floats, or pasos. We saw another paso in the church near our apartment. All through Andalucía (and many parts of Spain), Semana Santa is marked by ancient penance processions through the streets, performed by religious brotherhoods or fraternities. Each procession begins from its parish church, makes its way to the cathedral for a blessing and then back again. These processions can last up to 12 hours. Nazarenos, members of the brotherhood dressed in penitential robes consisting of a tunic, a hood with conical tip (capirote) used to conceal the face of the wearer, and sometimes a cloak, walk silently, usually in pairs, carrying processional candles, a long pole (vara) or a lantern. Following the nazarenos, and preceded by monaguillos (altar boys and girls), a magnificent paso or float is carried on the shoulders of the costaleros. Depending on the size and weight of the paso, there may be 100 or more costaleros. The pasos contain sculptures depicting different scenes from the gospels relating to the Passion of Christ or the sorrow of the Virgin Mary. Many of the floats are art pieces created by Spanish artists over the centuries. Usually, the pasos are accompanied by marching bands performing compositions devoted to the images and fraternities.

Our first morning in Seville, we decided to combine a long walk with a visit to the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo (CAAC), across the river towards the site of Expo 92. Some parts of the Expo site are used as a theme park, but others, including a park along the riverbank appear neglected. Eventually, we found our way to the Monasterio de Santa María de las Cuevas, which had been converted into a porcelain factory by Charles Pickman in 1839 and now houses the CAAC. There are still kiln chimneys rising above the buildings. In the gardens is an Ombú tree (or type of grass that grows to about 15 metres, native to South America), believed to have been planted by Hernando Colón, the son of Christopher Columbus.

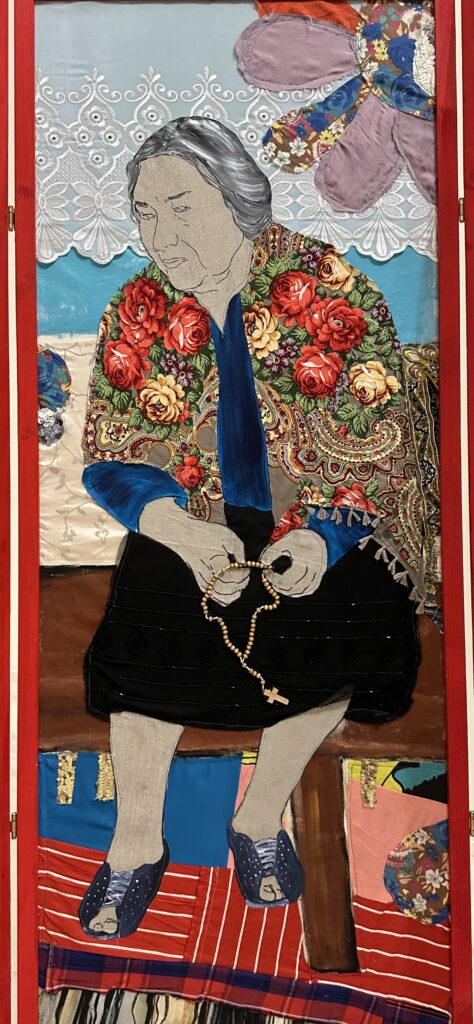

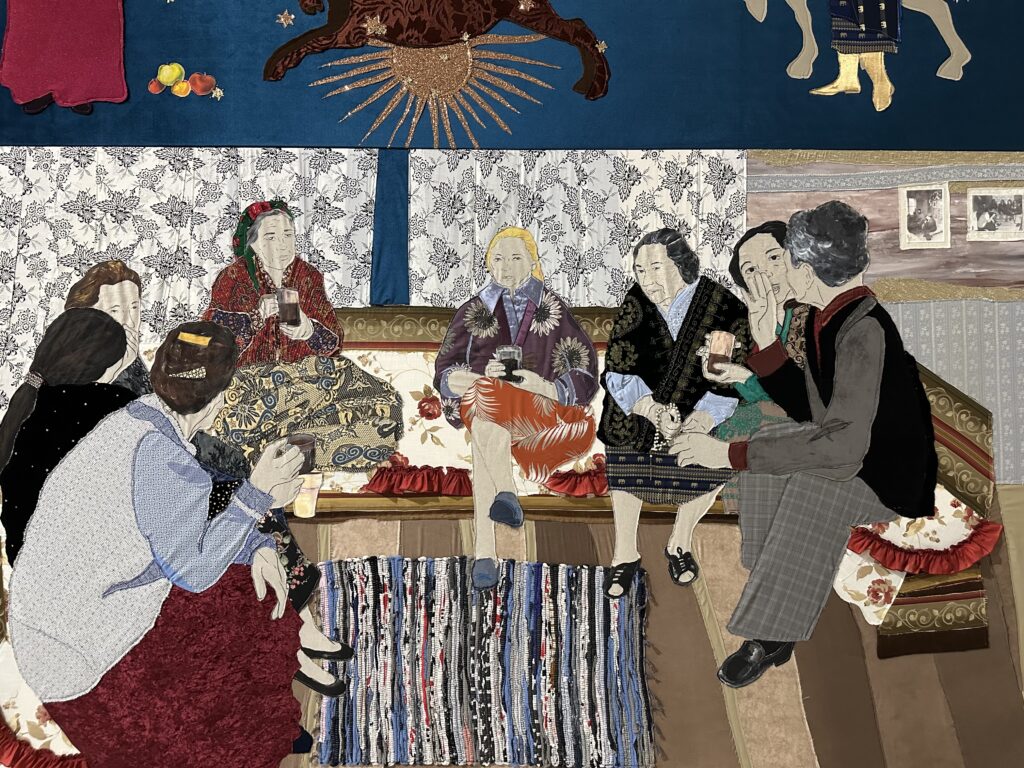

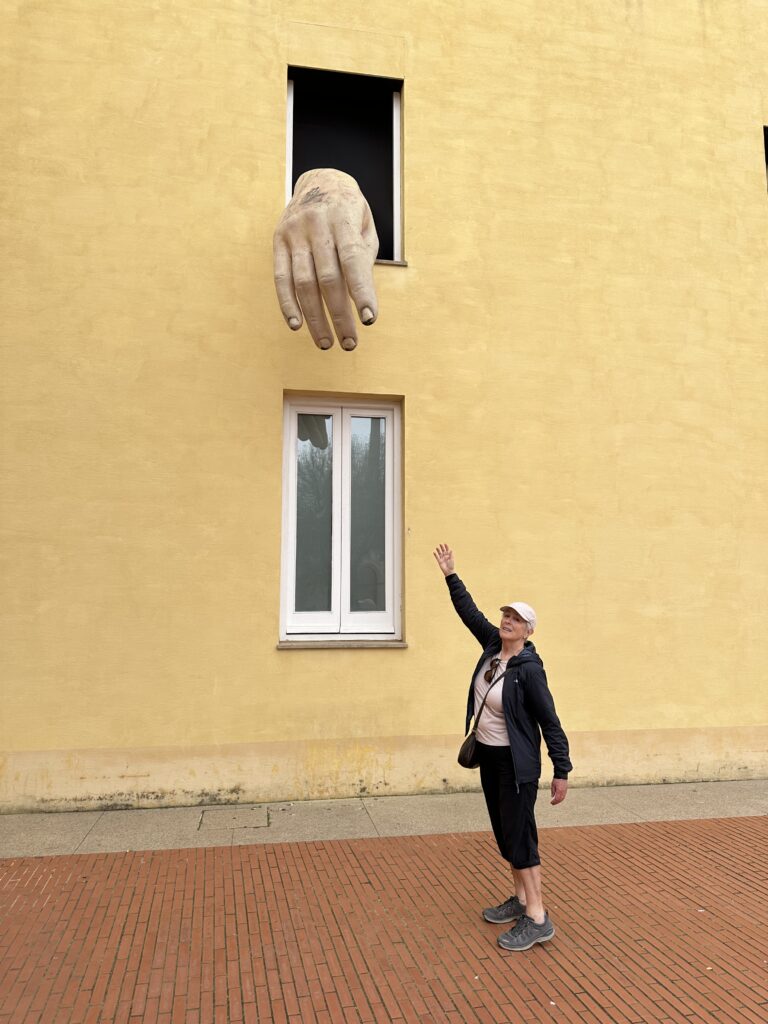

The art exhibits were extraordinary. The CAAC’s collection pays particular attention to the history of contemporary Andalusian art, in the context of Spain, Europe and the wider world. The exhibits are cleverly and artfully set out throughout the old monastery. One of the current exhibitions is a powerful installation of murals and sculptures by Malgorzata Mirga-Tas, a Romani activist and artist who challenges racist and colonial narratives of her people, particularly those of the women. Her murals, composed in colourful materials, dominate the walls of the main church and adjoining rooms. In another room, a lone sculpture represents the remains of a monument that she erected in a Polish forest commemorating a WWII massacre of her people. It was vandalized in 2016. Another exhibit showed a selection of works by more than 50 contemporary Latin American artists.

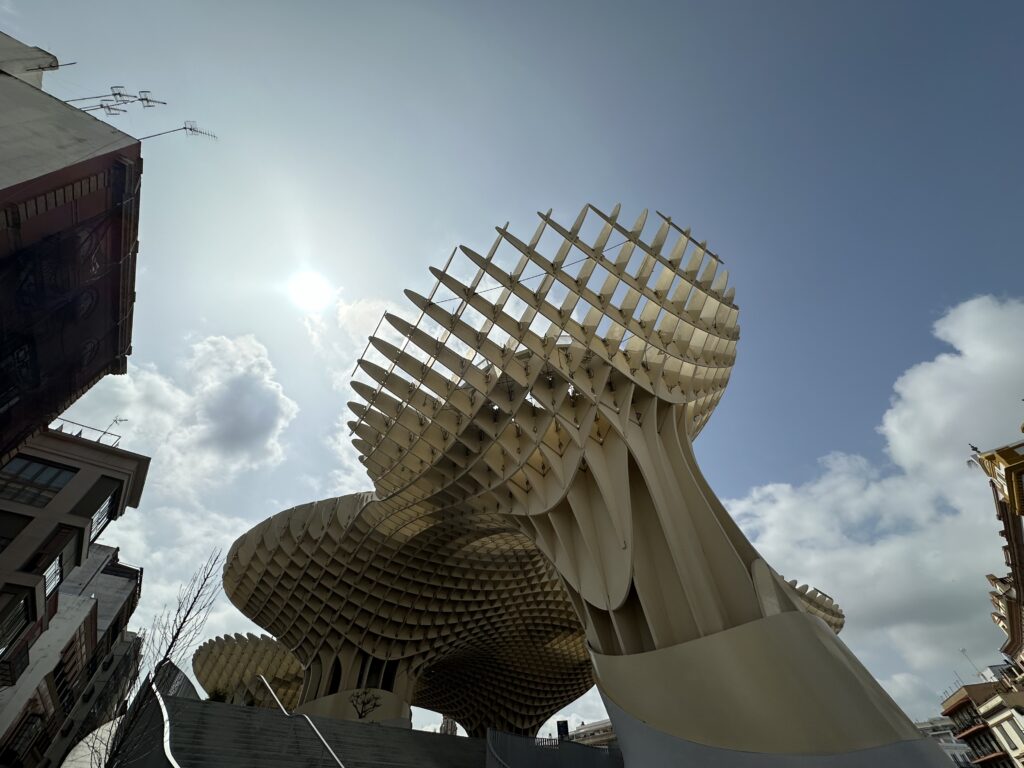

Taking a taxi back to centre of the old town, we headed to the Setas de Sevilla. This is an interesting but incongruous large structure housing a market and exhibition halls, with a viewing platform on top. Made of “micro-laminated” Finnish pine, it is apparently the largest wooden structure in the world. In the evening, we attended a flamenco performance recommended by our host, Tablao Flamenco Andalusí. Arriving early, we walked around the neighborhood and past the 18thC Plaza de Toros de la Real Maestranza de Caballeria de Sevilla, the 12,000 capacity bull ring still being used today.

The venue for the flamenco show was small and intimate, allowing the audience to be immersed in the experience. It began with a short video (fortunately with English subtitles) of the history of flamenco in Andalusia. The performance itself was mesmerizing, our attention flitting between the energetic footwork and dramatic gestures of the dancer, the virtuosity of the guitarist, the melancholic laments of the singer, and the rhythmic drumming of the flamenco box drum. Afterwards, we stopped at a local bar for tapas, including spinach and chickpeas and Spanish tortilla (omelette), with onions, garlic and whiskey! Paul notes here that 0% beer is available everywhere, even on tap. The best so far is Amstel, but the local Cruzcampo is a close second.

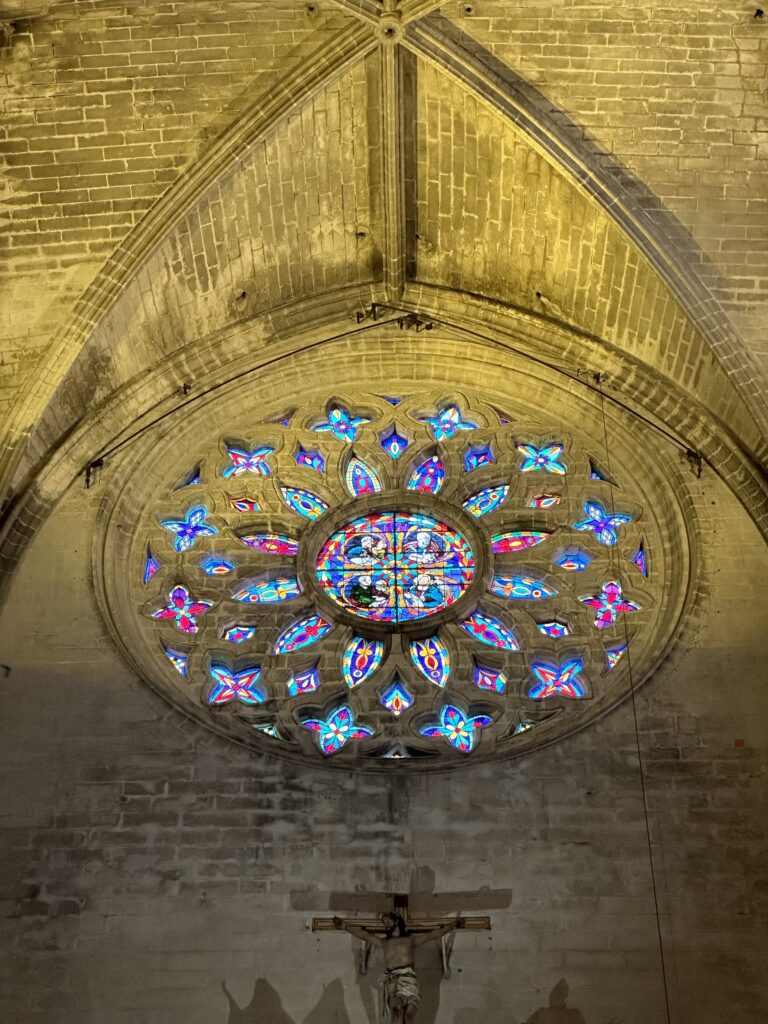

Two main draws in Seville are the Cathedral and the Real Alacazar and both were very busy. Compared to the Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba, the Seville Cathedral, Catedral de Santa Maria de la Sede, left us cold and overwhelmed. When the Catholic Kings of Spain reclaimed Seville from the Moors in 1248, they converted the existing grand 12thC mosque into a cathedral. Then, in 1406, the converted mosque was destroyed and a new cathedral constructed, one which would demonstrate the city’s wealth. Completed in the early 16thC, the cathedral is one of the largest churches in the world and the largest gothic church. The tomb of Christopher Columbus is in the cathedral. It is massive, with 80 chapels, but gave us no sense of cohesion and its grand decoration was intimidating, which was perhaps the idea. Some elements from the ancient mosque were preserved, eg, the courtyard for ablutions, known today as the Patio de los Naranjos, which contains a fountain and orange trees, and the minaret, which was converted into a bell tower known as the Giralda, now the city’s most well-known symbol.

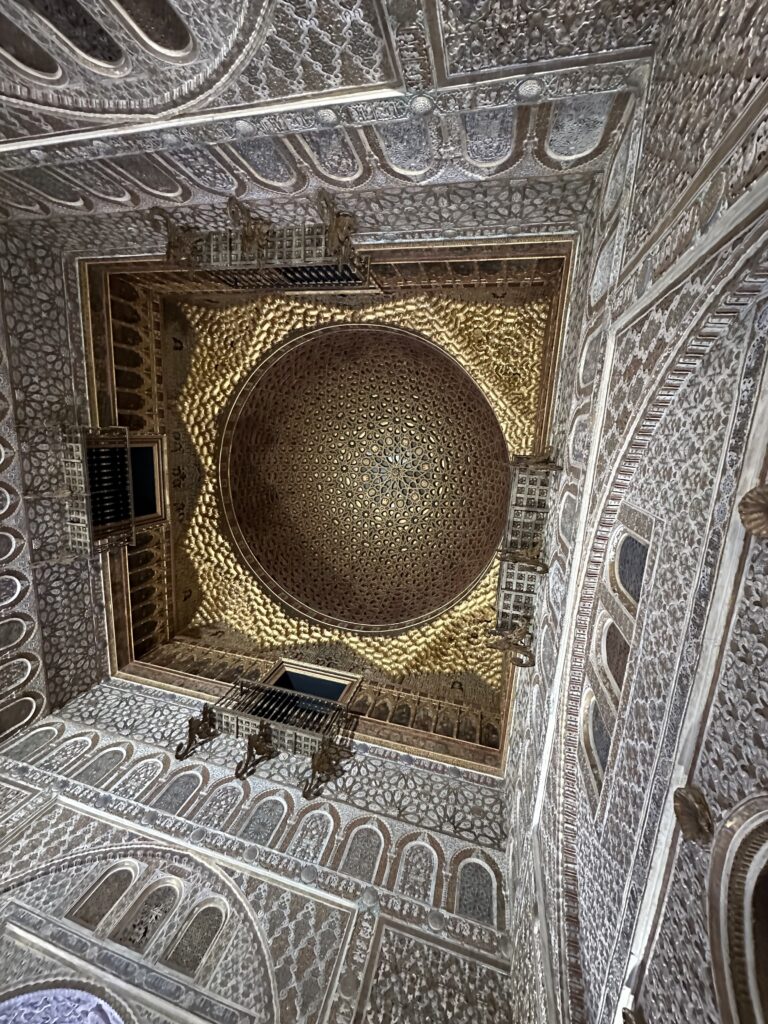

The Real (Royal) Alcázar of Savilla was formerly the site of the Islamic-era citadel of the city, begun in the 10th century and then developed into a larger palace complex on the 11th century. After the Castilian conquest of the city, it was progressively rebuilt and replaced by new palaces and gardens. Among the most important of these is a richly-decorated Mudéjar palace built during the 1360s. The Alcazar is a mixture of styles, but does give the sense of being a whole (unlike the Cathedral). It is known for its tile decoration. We were able to distinguish tiles made with the arista technique, where each coloured tile segment has raised ridges to avoid the mixing of different glaze colours during firing, and those using the majolica style, an innovation developed later in the 15th–16th centuries, which made it possible to “paint” directly on ceramics covered with white opaque glazes. “The Courtyard of the Maidens”, was part of the Mudéjar palace built by Pedro I in the 1360s. At ground level, several reception rooms are arranged around a long rectangular reflecting pool that runs the entire length of the patio. This pool is surrounded by promenades covered with a red brick pavement decorated with green ceramic borders. The garden and the pool were buried between 1581 and 1584 when the courtyard was paved with a white and black marble pavement, but the original structure was discovered and the hidden garden was uncovered after 2002–2005 excavations revealed the good state of conservation of the area under the patio and the ancient Mudejar garden was restored. Beyond the palace are extensive and peaceful gardens, one of which contain a large maze.

Needing reviving, we repaired to the Bar Alfalfa for tapas, a good “cervesa zero” and a glass of Albariño for Lois. This was followed by a marzipan and apple gelato for the walk back to our apartment. Before leaving for the bus station the next morning, we compared the espresso (and flat white) at two excellent coffee shops – East Crema Coffee Santa Maria (single origin Ethiopian 9.5) and Hispalis (Colombian and Ethiopian 9.5).