Waiting for the bus to Boulogne (from where we could catch a train to Arras), we looked across at the Eglise de Notre Dame de Licques, which is all that remains of an abbey, founded in 1075. The abbey and town suffered attacks from the English and Spanish in the 14thC, and the abbey was furthered damaged during the Revolution. As we waited, three fellow VF walkers approached from the direction of Guînes – a French woman who had started the walk to Rome from Callais (she would have begun from Canterbury, but had no passport), and two men from England who had begun walking from Winchester on Good Friday.

The bus trip to Boulogne, on time and comfortable, cost only 1€ each! Public transport is obviously valued here! Our bus driver even diverted from his usual route to drop us at the Gare SNCF. We then took two slow trains across country (changing at Le Touquet) arriving at Arras late afternoon where we had booked into the Le Dome hotel.

The following morning we checked out of Le Dome and moved into a lovely studio apartment (Les Anges) right off the Place des Héros, one of two grand cobbled squares in the centre of the city surrounded by Flemish Baroque-style townhouses. While the centre retains the appearance of a Baroque town, much of the centre had in fact been destroyed during WWI. Occupying a strategic position on the front line (earning it the name of « La ville martyr »), Arras was at the forefront of major battles during WWI, notably a major offensive action by the Allies during April and May 1917, during which Canadian forces gained Vimy Ridge. The remarkable rebuild was helped by the fact that, between 1556 to 1714, Arras was under Spanish rule and, during that time, Philip II of Spain decreed that all buildings be made of brick and stone and that they should all follow a similar identical style. This attention to detail meant that the town planners were able to rebuild the town in keeping with that style. Some buildings were reconstructed in the art deco style of the time. The Cathédrale Notre-Dame de L’Assomptiom (original cathedral destroyed during the Revolution) was also rebuilt after WWI.

Feeling in need of solace, our first visit was to the Musée de Beaux Arts. The gallery is housed in what was the Saint-Vaast Abbey (dating back to 7thC, it was burned down by the Normans in 783, later reconstructed according to plans designed by the great Parisian architect Labbé, attacked by the Vikings in the 9thC, survived the French Revolution, destroyed during WWI, then reconstructed in identical style!) We happily spent a few hours looking at Flemish and Dutch painting, e.g., Rubens’ Saint Francis receiving the Stigmata (1615), masters of the Arras school (19thC), including Désiré Dubois, Xavier Doulens and Charles Desavary, and a particularly fascinating contemporary exhibition of photos by Michel Gantner.

The next day, we took a taxi out to the Canadian National Vimy Memorial at the site of Canada’s victory during the Battle of Vimy Ridge in WWI. The soaring monument, designed by Canadian sculptor Walter Seymour Allwood, sits on the top of the highest point of the ridge, overlooking the Douai Plain. Erected between 1925 and 1936, the monument honours all Canadians who served in WWI. It is carved entirely from Croatian limestone, transported from an ancient Roman quarry in Seget, Croatia. The battle-damaged landscape around the sides and back of the monument were left untouched.

Two pylons representing Canada and France, bearing a Maple Leaf and a Fleur de Lys to honour the sacrifices made by both nations, rise 27 metres above the base. The monument includes 20 human figures representing such values as honour, justice, peace, truth, knowledge, gallantry and sympathy. The topmost figure is that of peace. An allegoric sculptural group marks each corner; Breaking of the Sword on the south corner, Sympathy of the Canadians for the Helpless on the north. Two reclining figures on the southern (reverse) side of the memorial, located either side of the steps, represent the mourning mothers and fathers of Canada’s war dead. The largest figure, known as “Canada Mourning her Fallen Sons” or “Canada Bereft”, stands alone, head bent in sorrow, looking out over the slopes of the ridge. Inscribed on the outside wall of the monument are the names of the 11,285 Canadians who died in France with no known grave. A departure from earlier practices, the monument was erected as a memorial rather than a victory monument, focussing on the loss of life and sacrifice for one’s country, rather than military accomplishments. The memorial, cemeteries, trenches, tunnels, craters and visitor’s centre are on Canadian soil, a gift from France, and managed by Veterans affairs. The tour guides are Canadian students here for 3 months at a time. From Vimy Ridge looking north one can see the slag heaps from the once important coal mining industry of the area. The old mines and associated human made topography are a UNESCO heritage site.

The rest of our time in Arras we spent resting, eating, reading and walking – a self-guided walking tour identified more ancient churches, the 19thC Fontaine du Pont-de-Cité (a fountain of Neptune, not impressive in itself, but notable as it was installed by the water authority to provide potable water to avoid cholera), Le Beffroi (Belfry) we couldn’t go up, as the elevator was not working) and the Citadelle d’Arras (which we travelled to on the Citadine, a free electric mini-bus). We declined to tour the “Boves” (a 20 km maze 10 m beneath the city), underground quarries dug out from the ninth century onwards, to extract material for the construction of the city’s religious buildings and the first rampart, later used as merchants’ storage cellars, and, finally, used by Commonwealth soldiers ahead of the first attack launching the famous Battle of Arras on 9 April 1917.

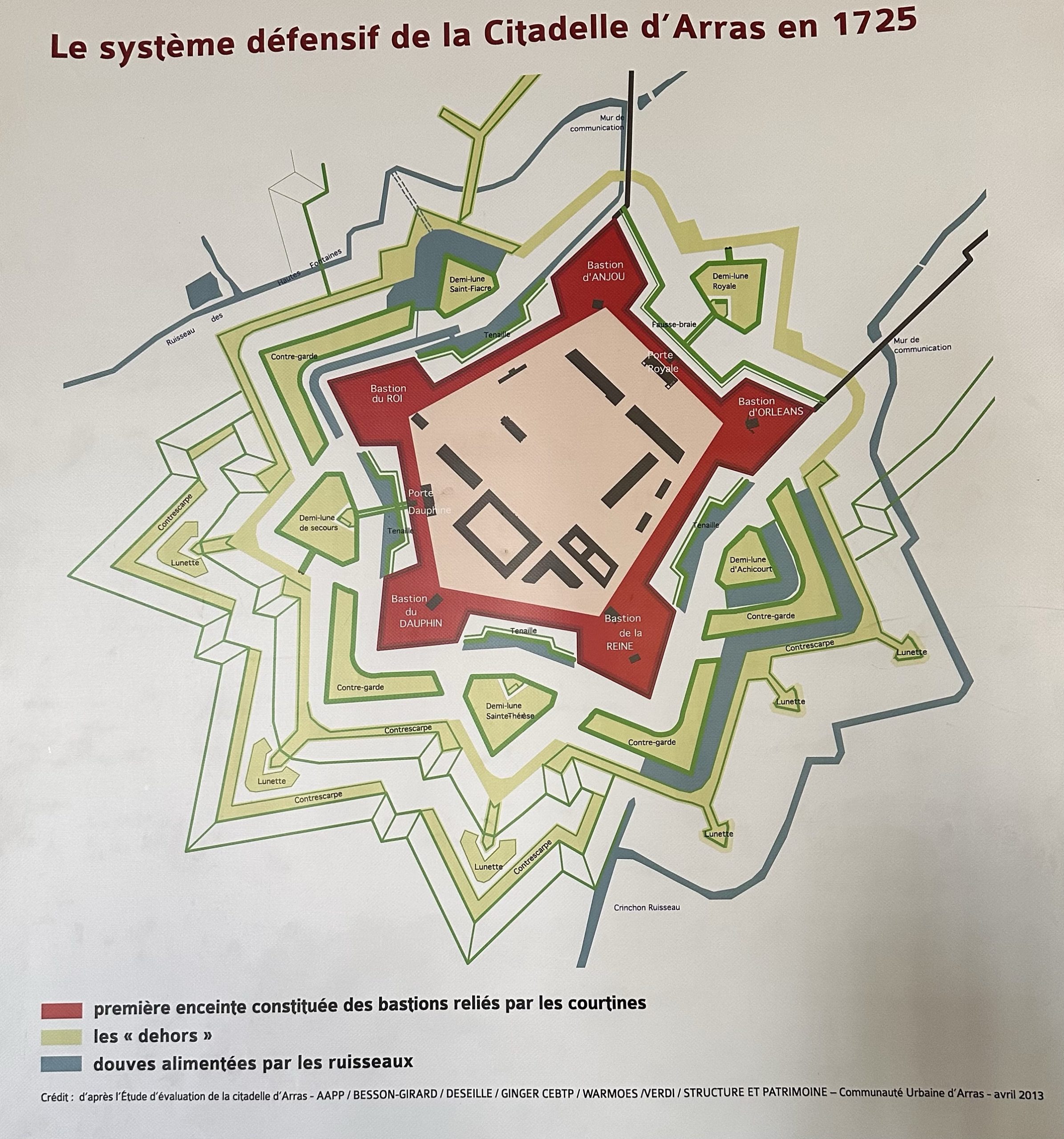

Arras was first fortified in the 13th century with city walls. These defences were improved in the 16th century by the Spanish rulers of the time but the French took the city in 1640, after which Louis XIV commissioned the renowned military strategist, Vauban, to protect Arras and France from attack by the then Spanish Netherlands.

The Citadel of Arras, another UNESCO World Heritage site, one of many built by Vauban, mostly in northern France in the late 17thC, was constructed as a pentagonal star. Never beseiged, thus nicknamed « la belle inutile » (useless beauty), the Citadel at times served as a prison and was used by the military up until 2010. During WWII, 218 people (aged between 16 and 69 yrs) suspected by the occupying Germans of being supporters of the Resistance were executed there by the Nazis. The Citadel Chapel of Saint-Louis (1673), still relatively intact, is the oldest church in Arras.

Feeling rested and hopefully recovered from the viruses we will resume walking tomorrow. Given the distance to Bapaume we may to do part of tomorrow’s stage by public transport.